For one reason or another I have not been fortunate enough to have had bluebirds as a regular part of the avifauna in most of the places where I've lived. My recollection from growing up in western Massachusetts is that Bluebirds were fairly common around the farm when I was quite young (i.e. in the late 1950s), and then they weren't; they became very rare visitors. My bird-loving father attributed the decline of Bluebirds to the increasing population of European Starlings, a species introduced to this country in the late 19th century, and the ensuing competition for cavity nesting sites. Contemporary ornithologists confirm his belief that Starlings were the bad guys in the scenario, though the problem arose before I was born. Fortunately, programs that began in the 1960s to distribute Bluebird-friendly nesting boxes have been quite successful in reversing the population decline. (Alas, my father was always frustrated in his own efforts to attract Bluebirds to the farm, because Tree Swallows invariably took over any nesting boxes that he put out. Not that that's a bad thing in and of itself.)

North by Northeast

A Yankee's perspectives on the natural and musical worlds, and on life in rural New England.

Saturday, March 5, 2022

"The Bluebird carries the sky on his back" -- Henry David Thoreau

Tuesday, March 9, 2021

Sugaring

There comes a time every year in late February or early March when the sun has climbed to a certain point in the sky, the temperature has risen enough to soften some of the snow and ice--and perhaps even create a bit of runoff alongside the road where the ground slopes downhill--and the smell of mud is in the air. When I step outside on a morning like that I immediately say to myself: "It feels like sugaring weather."

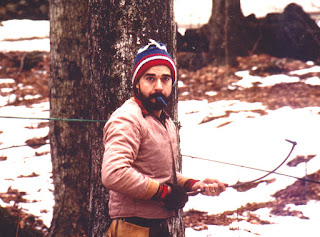

As I write, the maple sugaring season in New England is well underway. I grew up on a farm in western Massachusetts where making maple syrup was a regular and important part of the year's work. It was a time that we all looked forward to for various reasons, even though it meant a lot of hard work. Ours was a small, family operation (about 1,200 taps) that remained largely low-tech throughout the ±125 years that five generations of my family made syrup there. My father, Francis (seen here stoking the fire in the evaporator), was highly-respected among his peers. He was an honorary Lifetime Member of the Massachusetts Maple Producers Association. In addition to passing along love and knowledge of the craft to his children and grandchildren, he served as a mentor to numerous aspiring sugarmakers who came to him for advice and guidance. He was one of the sugarmakers chosen to represent Mass Maple at the 1988 Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife when Massachusetts was a featured state.I spent much of my early adulthood living in California so was not able to take part in sugaring for many years. In the early 1980s my first wife, young son, and I moved back to the farm. During the two years we lived there I took a much more active role in the sugaring operation than I had as a kid. During this period I was also trying to establish myself as a freelance writer, an endeavor that had more than its share of frustrations. I wrote the following short piece at a time when the frustrations were winning the day and my confidence was at a low ebb. I submitted it to the Berkshire Sampler, the weekly magazine associated with the Berkshire Eagle newspaper in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, for consideration for their "Dropping In" feature of reader submissions. The fact that it was accepted, and generated some good feedback among readers--one person who read it said that it made his hands hurt!--was worth far more to me than the twenty bucks I got paid for it. I've always been kind of proud of it as a piece of descriptive writing so I thought I'd send it out into the world again.

§§§§§

One night in late March, 1985

It's pushing 11:00 p.m. and I'm in the sugarhouse waiting to finish off one final batch of syrup before calling it quits for the night. Outside, the temperature feels as though it has dropped back below freezing, and the wind has come up.

Inside the sugarhouse, though, the heat of the fire in the evaporator has long since forced me to abandon my heavy wool shirt and I work with just a vest over a long underwear top. The intensity of the heat when I stoke the fire has melted the polypropylene fabric on the wrists of my shirt in spite of the long gauntlets on the heavy leather gloves I wear. Sticky patches of dried-on syrup cover my pants and shoes. The syrup forms an outer crust on top of the mud on my feet.

My hands suffer from a multitude of ills: slivers from the rough slabs used for firewood, steam burns from reaching over the boiling sap, cuts and bruises from sources too numerous to recall, dirt ground in so completely that no amount of scrubbing will get it out, and extreme chapping from being in and out of cold sap, warm water, and freezing snow all day.

The day in this case began some fifteen hours ago and is not over yet. Not every work day during sugaring season is this long, but neither is this an extraordinarily long one. The strain of doing five or six tasks simultaneously, while dealing with tourists, and staying one step ahead of the volunteer help offered by various folks whose eagerness to take part outstrips their familiarity with the process, has made me extremely weary. There is a particular type of exhaustion brought on by spending long periods of time in front of a raging fire. You feel parched, light-headed, thoroughly drained of energy. A night's sleep does not necessarily take the feeling away.The sugaring season is in the home stretch. Some of the less optimistic of the local maple sages are already proclaiming it to be over. My reactions to such pronouncements are decidedly mixed; we've reached only 75% of our production goal, but my enthusiasm is shrinking along with the woodpile.

The weekend has, in any event, been a good one. Probably every other sugarhouse in the Hilltowns is in operation tonight, and all my friends are no doubt feeling pretty much the same way I am. And, just as I'm certain that the syrup I'm boiling is sweet, I know that the first sugarmaker I talk with about the weekend will have worked a longer day, boiled more sap, made more syrup, burned more wood, and talked with more tourists than me. Guaranteed.

Make no mistake, sugaring is a lot of hard work, though it has its romantic aspects and everyone who sugars does so because they love it. There are few other sensations on earth as pleasant as walking into a sugarhouse where the sap is at a full, roiling boil, the room is filled with steam, and the sweet aroma of syrup-in-the-making fills your senses.

|

---

As the final batch of syrup nears completion I quit stoking the fire in preparation for shutting things down for the night. Once the fire simmers down, the temperature inside the sugarhouse begins to reach equilibrium with that outside. I put back on a couple of the layers of clothing I'd peeled off hours earlier.

When the syrup is ready, I draw it out of the evaporator into a pail, then pour it into the filter that sits on top of the canner. While trying to adjust the heavy felt filter to make use of a clean area, I lose my grip on the material. A gallon and a half of unfiltered syrup spills into the bottom of the canner, mixing with that which had already passed through. I have to draw off the entire contents from the canner, set up a clean filter, and run the whole batch through again.

That accomplished, I check the fire one last time, gather up the dirty filters to take to the house for washing, turn out the lights, and step outside. The night is clear and cold. The moon is only two days old so the stars shine brightly, with little competition. The distant "Who cooks for you?" call of a Barred Owl accompanies me on my short walk to the house.

In the kitchen I grab a beer from the refrigerator--stoking the fire is dehydrating work--and head to bed, trying not to wake anyone. I chug about half the beer which further numbs my already dulled senses. I take a quick shower--an absolute must--and crawl into bed. I unwind with the rest of my beer and a page or two of a mystery novel.

It's well after midnight when I turn out the light. I drift off, wondering if the sap will run again tomorrow. I'm asleep in less than a minute.

§§§§§

|

| Currier & Ives, "American Forest Scene - Maple Sugaring" |

§§§§§

I've always thought there should be fiddle tunes about maple sugaring so I finally wrote one. I composed this during a period when I was spending a lot of time looking at 19th century tunebooks from New England--Ryan's Mammoth Collection, Howe's School for the Violin, and the like--and I thought I'd try to write a tune that was stylistically similar to the ones in them. "Leather Apron" is an old-time term for the result of a simple test sugarmakers sometimes use to determine if syrup is ready to be drawn off. You scoop a dipper full of syrup out of the evaporator as it is boiling, then tilt the dipper so the liquid drips slowly off the edge, back into the pan. If it comes off in a sheet--i.e., a "leather apron"--rather than in droplets, it is nearly ready. (Click on the tune for a larger image.)

Tuesday, January 5, 2021

Apples in Winter

|

| Orchard at Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, New Gloucester, Maine, December 1, 2018 |

This strong presence of apples in my early life has given me a deep, sentimental fascination with apples and old apple trees. At times it seems as though the trees have a living spirit or personality of their own. They stand, silent and unmoving, as they have for perhaps a century or more, voiceless witnesses to decades of change in the social and economic worlds around them. Their character is especially revealed in winter when the leaves are gone and we see the venerable old things in all their crooked, twisty splendor. The fruit of some varieties clings to the branches well into early winter, as is the case with those pictured here that stand in the orchard at Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in New Gloucester, Maine. This gives one the sense that the trees are refusing to yield to the change of seasons but want to retain the past summer's bounty for as long as possible. I take this as a lesson in persistence. How very Shaker-like.

It's impossible to know just how many different types of apples were once grown in this country--I have seen estimates as high as 16,000--but the ±50 varieties in the family orchard is probably a fairly typical number for many older New England farms. A big reason for the bewildering diversity is the nature of apples themselves; if left to their own devices apple seeds don't reproduce replicas of the trees they came from. Apples are "extreme heterozygotes," meaning that they reproduce with unpredictable characteristics. If you have a type of apple that you like and want to be able to keep growing more with the same traits, you have to do so via grafting (i.e., cloning). But their heterozygosity(!) makes it possible to cultivate many different varieties, each with its own attributes. By the same token, if orchardists and nursery owners stop cultivating particular types they will become extinct. Hence the importance of the work of Bunker and Fedco.

While some Biblical scholars suggest that it would be more appropriate for the tree in the tale of Adam and Eve's expulsion from the Garden of Eden in Judeo-Christian mythology to be identified as a fig rather than an apple, the cultivation of apples is, in fact, thousands of years old. Apples may well have been the first fruit tree to be cultivated, beginning in what is today Kazakhstan. It is said that apples were introduced to England during the reign of Julius Caesar. Colonists from Britain brought them to the New World early in the 17th century.

|

| "Cider Making," William Sidney Mount, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Apples in overgrown orchard at Laudholm Farm, Wells, Me |

But cultivate apples Yankee farmers certainly did. The orchard on my family's farm was probably fairly typical in terms of size and of the diversity of varieties grown in it. A treasure found among the stash of family documents that came to me when my father passed away and we dispersed the contents of the farm house, is a map of the orchard with a key to the types, location, and quantity of the trees it contained (a typescript of the list is included at the end of this post):

A more benign activity, and one that required a certain amount of skill, was Apple Throwing; i.e., using a supple stick as a quasi-catapult to hurl apples for distance. This is best done with apples that are about half mature. We'd go into the woods, pocket knives in hand, cut two or three small saplings, maybe 3'-4' long, and sharpen one end of each in order to impale an apple on it. Selecting a stick that was just the right thickness, with just the right degree of flexibility, and then trimming it to just the right length, was a bit of an art. Additional skill was needed to push the apple onto the sharpened tip just far enough so it would not come off prematurely, but not so far that it wouldn't come off at all. Then, using either an overhand or sidearm technique, you'd reach waaaay back, whip the stick rapidly forward, and, with a well-timed flick of the wrist, send the apple flying across the field. If all the variables of suppleness, stick length, apple weight, throwing power, and technical prowess, were in perfect balance, your apple would go whistling through the air at a great rate--far enough, one hoped, that it would clear the stone wall on the opposite side of the field. Or at least travel as far as your older brother's did.

A more benign activity, and one that required a certain amount of skill, was Apple Throwing; i.e., using a supple stick as a quasi-catapult to hurl apples for distance. This is best done with apples that are about half mature. We'd go into the woods, pocket knives in hand, cut two or three small saplings, maybe 3'-4' long, and sharpen one end of each in order to impale an apple on it. Selecting a stick that was just the right thickness, with just the right degree of flexibility, and then trimming it to just the right length, was a bit of an art. Additional skill was needed to push the apple onto the sharpened tip just far enough so it would not come off prematurely, but not so far that it wouldn't come off at all. Then, using either an overhand or sidearm technique, you'd reach waaaay back, whip the stick rapidly forward, and, with a well-timed flick of the wrist, send the apple flying across the field. If all the variables of suppleness, stick length, apple weight, throwing power, and technical prowess, were in perfect balance, your apple would go whistling through the air at a great rate--far enough, one hoped, that it would clear the stone wall on the opposite side of the field. Or at least travel as far as your older brother's did.

1.

Greening -- 29

2.

Roxbury Russett – 19*

3.

Seeknofurther -- 5

4.

Sweet Russett -- 6

5.

Family Apple – 9

6.

Vandiver – 3

7.

Nursery – 3

8.

Spitsenburg [sic] – 11

9.

Sops of Wine – 2

10.

Fall Pippin – 7

11.

Lady Finger Pairmain [Pearmain] – 4

12.

Juneating – 3

13.

Baldwin – 23

14.

Gravenstein –

15.

Spur Sweet – 3

16.

Lady Apple – 2

17.

Esq. Packard Apple – 8

18.

Fall or Winter Sheep – 2

19.

Porter Apple – 2

20.

Norman W Apple – 2

21.

Orange Sweet – 5

22.

Little Core – 5

23.

Name unknown – 2

24.

Reed cheack [sic] Russett – 1

*Said to be the oldest

known variety in America

|

25.

Robbins sweet Russett – 1

26.

Early Bough – 5

27.

Orange Sour – 3

28.

N.Y. Pippin – 3

29.

D Towers sweat [sic] Russett – 3

30.

Monstrous Pippin – 3

31.

Green Seeknofurther – 2

32.

Bullock Pippin – 2

33.

Loomis Sweet – 2

34.

Summer Golden sweet – 3

35.

Summer Pearmain – 2

36.

Winter Sweet – 2

37.

Barr –

38.

Winter Pearmain –

39.

Orange Winter – 1 **

41.

Richardson – 1

42.

Jewits [Jewett's] fine Red – 1

43.

Grandfather Cobb – 1 (Pear)

44.

Howard -- 1 (Pear)

46.

Mother Apple – 2

47.

Danvers Sweet – 7

48.

Esopus Spitzenburg – [ ]

49.

Northern Spy – 3

** there is no entry #40

|

Tuesday, December 15, 2020

The Tune in the Christmas Cracker

This post is something I put up as a "Note" on Facebook back in 2013. It generated a considerable and gratifying amount of discussion among my friends who are into Irish music. Because it's been several years since I posted it, and because Facebook recently made some changes that have rendered "notes" extremely difficult for people to find, I've decided to re-post the story here. I take this opportunity to add some illustrations. Comments are again very much welcome! -- December, 2020

---

Some years ago I bought a copy of Capt. Francis O'Neill's Dance Music of Ireland off eBay from a seller somewhere in the UK. This was not a first edition of the 1001 Gems, but is a relatively old one. It's identified on the cover as the "11th Edition." This edition was "Edited and arranged by" Selena O'Neill (a protege of, but no relation to, the good Captain), and published by her in 1940. It carries a hand-written ownership statement identifying it as having once been the property of one J. McTernan, of Oscott College, Sutton Coldfield. Google maps tells me that this is just northeast of Birmingham, England.While this is cool in and of itself, the book carried a hidden treasure--a single sheet of music manuscript paper on which are two meticulously hand-written tunes. The toy inside the Christmas cracker, as it were. Because one of the tunes is the reel that Irish musicians all know as "Christmas Eve"--identified on the sheet by the name of its composer, Tommy Cohen (sic: Coen)--we offer it here as a small seasonal gift for all our friends, musicians and non-musicians alike. (See below for a reproduction of the entire manuscript page.)

Saturday, August 29, 2020

August: The Golden Month

August is the Golden Month. It is the month when Goldenrod fills open fields, turning them into oceans of amber. It's the month when Black-eyed Susans grow wild in meadows and along roadsides, and bring a big splash of cheer to our home gardens.

But not all the August flora is golden. Queen Anne's Lace, with its complex, delicate, seemingly otherworldly beauty, blooms alongside the Goldenrod and Black-eyed Susans.

Numerous other seasonal events also define August. It is the month when the Perseid meteor showers tempt us to venture out late at night, in the hope of witnessing a celestial light show. It is the month for marveling at the acrobatic maneuvers of flocks of Nighthawks, as they hunt insects at dusk; their long, pointy wings with transverse white stripes make them unmistakable even to casual observers. It is the time for mowing rowen, and the chance to enjoy another display of avian acrobatics, from swallows this time, before they make their early exit from New England and head south for the winter. It's the month of agricultural fairs, of corn on the cob, of ripening apples, of wearing t-shirts and shorts during the hot days and bundling up in sweaters and sweatshirts during the chilly nights.

For so many years, when the cycle of my life was tied to the academic calendar, August was a time of, if not exactly dread, of less-than-eager anticipation of the changes that September would inevitably bring. As a kid, the prospect of exchanging the carefree, unstructured time of Summer for the regimen of the school day was unwelcome, to say the least. As an adult, working in a university, August meant that the relative quiet of a thinly-populated summer campus would soon be transformed into a time of chaos and commotion, as hordes of students returned, and faculty and staff were plunged into a seemingly endless series of meetings and receptions.