There comes a time every year in late February or early March when the sun has climbed to a certain point in the sky, the temperature has risen enough to soften some of the snow and ice--and perhaps even create a bit of runoff alongside the road where the ground slopes downhill--and the smell of mud is in the air. When I step outside on a morning like that I immediately say to myself: "It feels like sugaring weather."

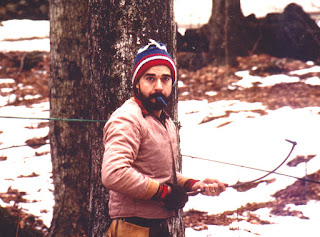

As I write, the maple sugaring season in New England is well underway. I grew up on a farm in western Massachusetts where making maple syrup was a regular and important part of the year's work. It was a time that we all looked forward to for various reasons, even though it meant a lot of hard work. Ours was a small, family operation (about 1,200 taps) that remained largely low-tech throughout the ±125 years that five generations of my family made syrup there. My father, Francis (seen here stoking the fire in the evaporator), was highly-respected among his peers. He was an honorary Lifetime Member of the Massachusetts Maple Producers Association. In addition to passing along love and knowledge of the craft to his children and grandchildren, he served as a mentor to numerous aspiring sugarmakers who came to him for advice and guidance. He was one of the sugarmakers chosen to represent Mass Maple at the 1988 Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife when Massachusetts was a featured state.I spent much of my early adulthood living in California so was not able to take part in sugaring for many years. In the early 1980s my first wife, young son, and I moved back to the farm. During the two years we lived there I took a much more active role in the sugaring operation than I had as a kid. During this period I was also trying to establish myself as a freelance writer, an endeavor that had more than its share of frustrations. I wrote the following short piece at a time when the frustrations were winning the day and my confidence was at a low ebb. I submitted it to the Berkshire Sampler, the weekly magazine associated with the Berkshire Eagle newspaper in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, for consideration for their "Dropping In" feature of reader submissions. The fact that it was accepted, and generated some good feedback among readers--one person who read it said that it made his hands hurt!--was worth far more to me than the twenty bucks I got paid for it. I've always been kind of proud of it as a piece of descriptive writing so I thought I'd send it out into the world again.

§§§§§

One night in late March, 1985

It's pushing 11:00 p.m. and I'm in the sugarhouse waiting to finish off one final batch of syrup before calling it quits for the night. Outside, the temperature feels as though it has dropped back below freezing, and the wind has come up.

Inside the sugarhouse, though, the heat of the fire in the evaporator has long since forced me to abandon my heavy wool shirt and I work with just a vest over a long underwear top. The intensity of the heat when I stoke the fire has melted the polypropylene fabric on the wrists of my shirt in spite of the long gauntlets on the heavy leather gloves I wear. Sticky patches of dried-on syrup cover my pants and shoes. The syrup forms an outer crust on top of the mud on my feet.

My hands suffer from a multitude of ills: slivers from the rough slabs used for firewood, steam burns from reaching over the boiling sap, cuts and bruises from sources too numerous to recall, dirt ground in so completely that no amount of scrubbing will get it out, and extreme chapping from being in and out of cold sap, warm water, and freezing snow all day.

The day in this case began some fifteen hours ago and is not over yet. Not every work day during sugaring season is this long, but neither is this an extraordinarily long one. The strain of doing five or six tasks simultaneously, while dealing with tourists, and staying one step ahead of the volunteer help offered by various folks whose eagerness to take part outstrips their familiarity with the process, has made me extremely weary. There is a particular type of exhaustion brought on by spending long periods of time in front of a raging fire. You feel parched, light-headed, thoroughly drained of energy. A night's sleep does not necessarily take the feeling away.The sugaring season is in the home stretch. Some of the less optimistic of the local maple sages are already proclaiming it to be over. My reactions to such pronouncements are decidedly mixed; we've reached only 75% of our production goal, but my enthusiasm is shrinking along with the woodpile.

The weekend has, in any event, been a good one. Probably every other sugarhouse in the Hilltowns is in operation tonight, and all my friends are no doubt feeling pretty much the same way I am. And, just as I'm certain that the syrup I'm boiling is sweet, I know that the first sugarmaker I talk with about the weekend will have worked a longer day, boiled more sap, made more syrup, burned more wood, and talked with more tourists than me. Guaranteed.

Make no mistake, sugaring is a lot of hard work, though it has its romantic aspects and everyone who sugars does so because they love it. There are few other sensations on earth as pleasant as walking into a sugarhouse where the sap is at a full, roiling boil, the room is filled with steam, and the sweet aroma of syrup-in-the-making fills your senses.

|

---

As the final batch of syrup nears completion I quit stoking the fire in preparation for shutting things down for the night. Once the fire simmers down, the temperature inside the sugarhouse begins to reach equilibrium with that outside. I put back on a couple of the layers of clothing I'd peeled off hours earlier.

When the syrup is ready, I draw it out of the evaporator into a pail, then pour it into the filter that sits on top of the canner. While trying to adjust the heavy felt filter to make use of a clean area, I lose my grip on the material. A gallon and a half of unfiltered syrup spills into the bottom of the canner, mixing with that which had already passed through. I have to draw off the entire contents from the canner, set up a clean filter, and run the whole batch through again.

That accomplished, I check the fire one last time, gather up the dirty filters to take to the house for washing, turn out the lights, and step outside. The night is clear and cold. The moon is only two days old so the stars shine brightly, with little competition. The distant "Who cooks for you?" call of a Barred Owl accompanies me on my short walk to the house.

In the kitchen I grab a beer from the refrigerator--stoking the fire is dehydrating work--and head to bed, trying not to wake anyone. I chug about half the beer which further numbs my already dulled senses. I take a quick shower--an absolute must--and crawl into bed. I unwind with the rest of my beer and a page or two of a mystery novel.

It's well after midnight when I turn out the light. I drift off, wondering if the sap will run again tomorrow. I'm asleep in less than a minute.

§§§§§

|

| Currier & Ives, "American Forest Scene - Maple Sugaring" |

§§§§§

I've always thought there should be fiddle tunes about maple sugaring so I finally wrote one. I composed this during a period when I was spending a lot of time looking at 19th century tunebooks from New England--Ryan's Mammoth Collection, Howe's School for the Violin, and the like--and I thought I'd try to write a tune that was stylistically similar to the ones in them. "Leather Apron" is an old-time term for the result of a simple test sugarmakers sometimes use to determine if syrup is ready to be drawn off. You scoop a dipper full of syrup out of the evaporator as it is boiling, then tilt the dipper so the liquid drips slowly off the edge, back into the pan. If it comes off in a sheet--i.e., a "leather apron"--rather than in droplets, it is nearly ready. (Click on the tune for a larger image.)

Lovely stuff as always.

ReplyDeleteThanks! Um....Chris?

DeleteA generation and more back my family boiled sap in the sugar bushes of the Eastern Townships of Quebec. I can just small the aroma in the air!

ReplyDeleteThanks for reading and commenting!

DeleteGreat piece! I could feel the sweet steam on my face in the sugarhouse. My favorite part, though was the 'baby Paul' photo!

ReplyDeleteThanks, my unknown reader! :)

DeleteNow I need to make French Toast. Thank you for posting. In this day & age when us city folk tend to think everything comes from a factory, it's good to be reminded of the hard work involved in sugaring.

ReplyDeleteGo for it! (The French Toast, that is!) Thanks for reading and commenting,

DeleteYou look good Paul Wells, glad we all have fond childhood memories of the things we have done. That is much more than the kids of todays world!!

ReplyDeleteYour Dad was a very hard worker and that is something to be very proud of....

Thanks, Deb! Yeah, my Dad was a fine role model. We were, indeed, fortunate to have grown up when, where, and how we did.

DeleteJust beautiful 💜

DeleteThanks, my Anonymous reader! :)

DeleteI could almost smell the \sap boiling. I'm a long way from home these days, but those memories stay strong.

ReplyDeleteThanks!

DeleteSome lovely and cherished childhood memories were evoked here today, thank you

ReplyDeleteThanks, my unknown reader!

Delete